-

Neueste Beiträge

Archive

- Juli 2025

- Juni 2025

- Mai 2025

- April 2025

- März 2025

- Februar 2025

- Januar 2025

- Dezember 2024

- November 2024

- Oktober 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- Juli 2024

- Juni 2024

- Mai 2024

- April 2024

- März 2024

- Februar 2024

- Januar 2024

- Dezember 2023

- November 2023

- Oktober 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- Juli 2023

- Juni 2023

- Mai 2023

- April 2023

- März 2023

- Februar 2023

- Januar 2023

- Dezember 2022

- November 2022

- Oktober 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- Juli 2022

- Juni 2022

- Mai 2022

- April 2022

- März 2022

- Februar 2022

- Januar 2022

- Dezember 2021

- November 2021

- Oktober 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- Juli 2021

- Juni 2021

- Mai 2021

- April 2021

- März 2021

- Februar 2021

- Januar 2021

- Dezember 2020

- November 2020

- Oktober 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- Juli 2020

- Juni 2020

- Mai 2020

- April 2020

- März 2020

- Februar 2020

- Januar 2020

- Dezember 2019

- November 2019

- Oktober 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- Juli 2019

- Juni 2019

- Mai 2019

- April 2019

- März 2019

- Februar 2019

- Januar 2019

- Dezember 2018

- November 2018

- Oktober 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- Juli 2018

- Juni 2018

- Mai 2018

- April 2018

- März 2018

- Februar 2018

- Januar 2018

- Dezember 2017

- November 2017

- Oktober 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- Juni 2017

- Mai 2017

- April 2017

- März 2017

- Februar 2017

- Januar 2017

- Dezember 2016

- November 2016

- Oktober 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- Juli 2016

- Juni 2016

- Mai 2016

- April 2016

- März 2016

- Februar 2016

- Januar 2016

- Dezember 2015

- November 2015

- Oktober 2015

- August 2015

- Juli 2015

- Juni 2015

- April 2015

- Januar 2015

- Dezember 2014

- November 2014

- Oktober 2014

- September 2014

- Juli 2014

- Juni 2014

- Mai 2014

- April 2014

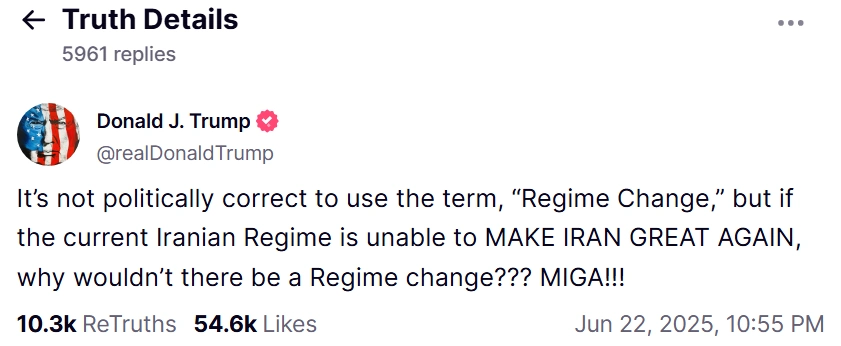

US is „not at war“ with Iran, vice president says

CNN:

Vice President JD Vance, in his first public comments since President Donald Trump authorized US strikes on Iranian nuclear sites, emphasized that the US is “not at war” with Iran as he laid out the president’s decision-making process.

“We’re not at war with Iran. We’re at war with Iran’s nuclear program,” Vance said in an interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press with Kristen Welker,” calling the strikes a “testament to the power of the American military.”

…

Vance added, “Of course we trust our intelligence community, but we also trust our instincts. … The Iranians stopped negotiating in good faith – that was the real catalyst.”

The vice president also suggested that Trump arrived at the conclusion to authorize the strikes after issuing what he described as “private ultimatums” to Iran. He declined to detail those ultimatums.

Kommentare deaktiviert für US is „not at war“ with Iran, vice president says

In Exile

‚If,‘ says I, ‚if Fate has wronged you and me cruelly, it’s no good asking for her favor and bowing down to her, but you despise her and laugh at her, or else she will laugh at you.‘

—Anton Chekhov, „In Exile“, Ward No. 6 and Other Stories, (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2003), 74.

Kommentare deaktiviert für In Exile

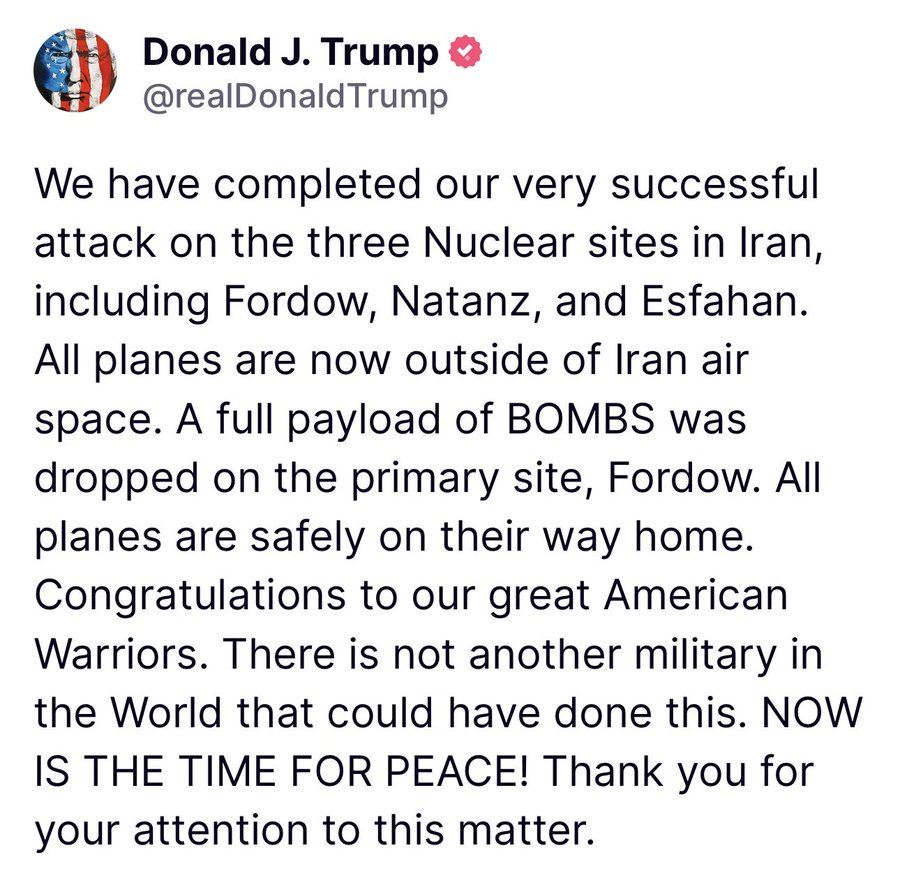

The American public is finding out who their military is bombing from social media.

Kommentare deaktiviert für The American public is finding out who their military is bombing from social media.

Meditation, Workshops und tiefer Präsenz für das Wohl aller Menschen, Tiere und der Natur

Kommentare deaktiviert für Meditation, Workshops und tiefer Präsenz für das Wohl aller Menschen, Tiere und der Natur

Democracy dies in darkness. All the news that’s fit to print.

https://www.sfgate.com/

https://www.inquirer.com/

On June 20, 2025, after days of Israel bombing Iran, Iran hitting Israel with missiles, the US threatening bombing, the San Francisco Gate and Philadelphia Inquirer home pages do not mention the word „Iran“. Go ahead, search for it. I did.

Kommentare deaktiviert für Democracy dies in darkness. All the news that’s fit to print.

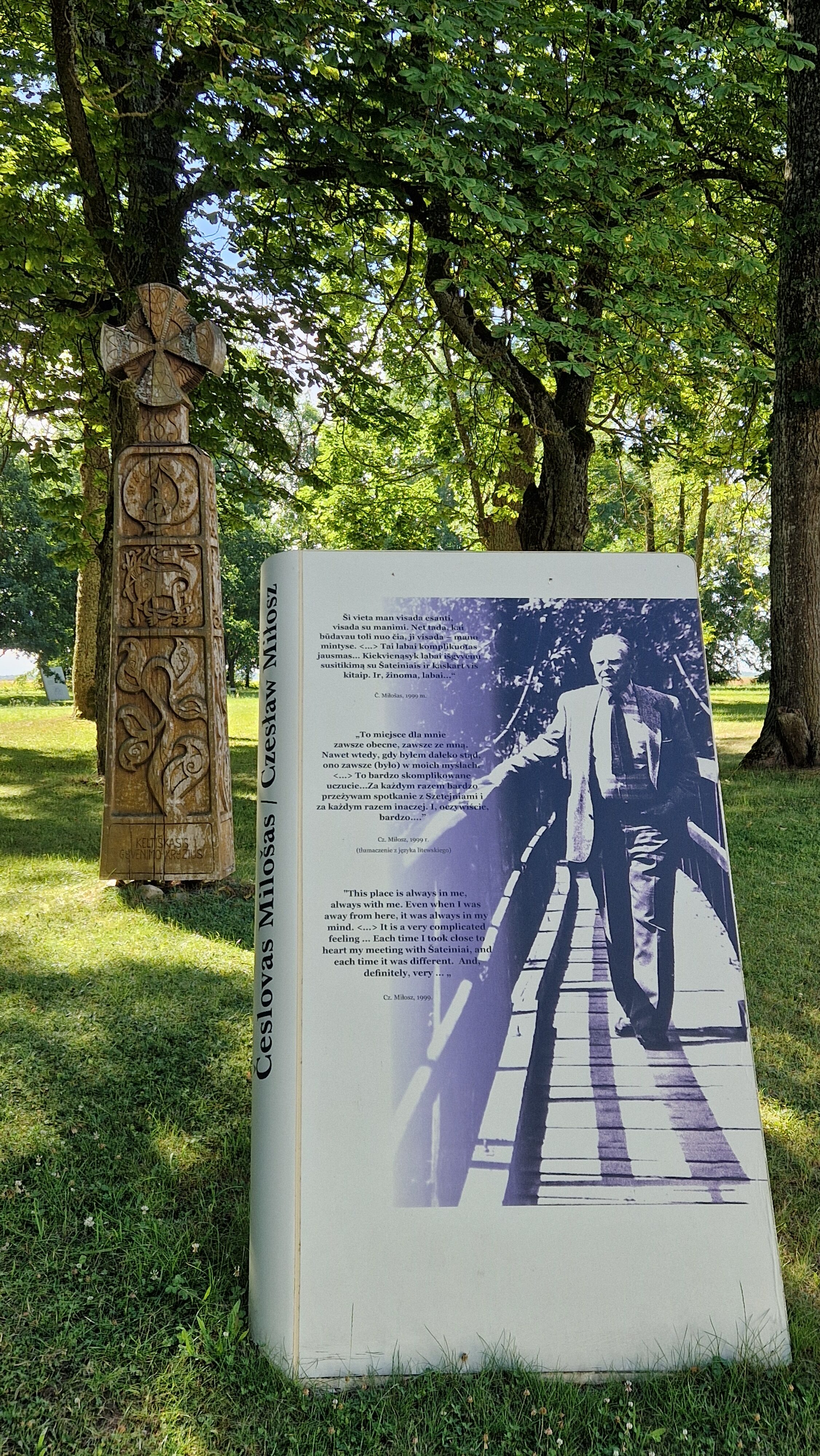

Czesław Miłosz birthplace, Šeteniai

A Song on the End of the World

On the day the world ends

A bee circles a clover,

A fisherman mends a glimmering net.

Happy porpoises jump in the sea,

By the rainspout young sparrows are playing

And the snake is gold-skinned as it should always be.On the day the world ends

Women walk through the fields under their umbrellas,

A drunkard grows sleepy at the edge of a lawn,

Vegetable peddlers shout in the street

And a yellow-sailed boat comes nearer the island,

The voice of a violin lasts in the air

And leads into a starry night.And those who expected lightning and thunder

Are disappointed.

And those who expected signs and archangels’ trumps

Do not believe it is happening now.

As long as the sun and the moon are above,

As long as the bumblebee visits a rose,

As long as rosy infants are born

No one believes it is happening now.Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.—Czesław Miłosz, translated by Anthony Miłosz

Warsaw, 1944

Kommentare deaktiviert für Czesław Miłosz birthplace, Šeteniai

Pętla po Puszczy Noteckiej ze Starego Polichna

Kommentare deaktiviert für Pętla po Puszczy Noteckiej ze Starego Polichna

„Outside the room, he [the senior US Senator from California] is pinned to the floor and placed in handcuffs.“

Kommentare deaktiviert für „Outside the room, he [the senior US Senator from California] is pinned to the floor and placed in handcuffs.“